The indestructible light beam

14.04.2021 - Special light waves can penetrate even opaque materials as if the material was not even there.

Why is sugar not transparent? Because light that penetrates a piece of sugar is scattered, altered and deflected in a highly complicated way. However, as a research team from TU Wien and Utrecht University has now been able to show, there is a class of very special light waves for which this does not apply: for any specific disordered medium tailor-made light beams can be constructed that are practically not changed by this medium, but only attenuated. The light beam penetrates the medium, and a light pattern arrives on the other side that has the same shape as if the medium were not there at all. This idea of scattering-invariant modes of light can also be used to specifically examine the interior of objects.

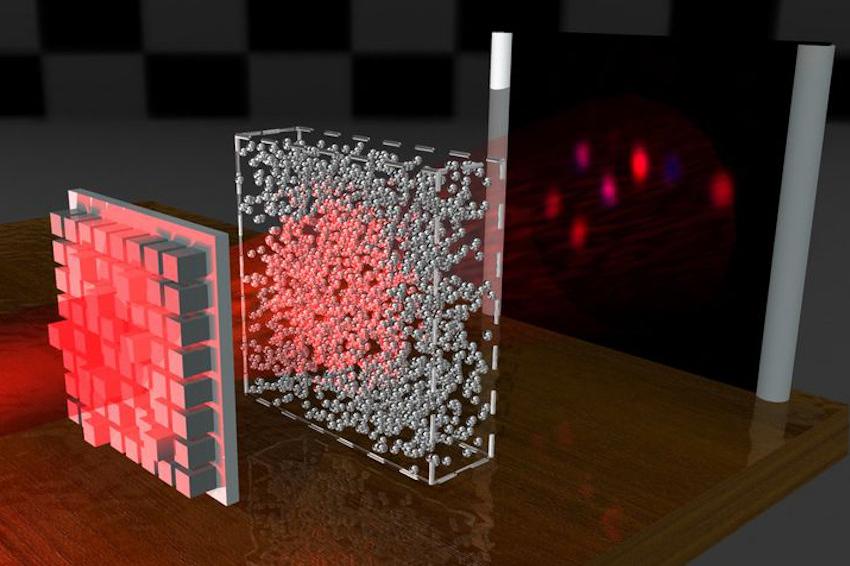

The waves on a turbulent water surface can take on an infinite number of different shapes – and in a similar way, light waves can also be made in countless different forms. “Each of these light wave patterns is changed and deflected in a very specific way when you send it through a disordered medium,” explains Stefan Rotter from the Institute of Theoretical Physics at TU Wien. Together with his team, Stefan Rotter is developing mathematical methods to describe such light scattering effects. The expertise to produce and characterise such complex light fields was contributed by the team around Allard Mosk at Utrecht University. “As a light-scattering medium, we used a layer of zinc oxide – an opaque, white powder of completely randomly arranged nanoparticles,” explains Allard Mosk, the head of the experimental research group.

First, you have to characterize this layer precisely. You shine very specific light signals through the zinc oxide powder and measure how they arrive at the detector behind it. From this, you can then conclude how any other wave is changed by this medium – in particular, you can calculate specifically which wave pattern is changed by this zinc oxide layer exactly as if wave scattering was entirely absent in this layer. “As we were able to show, there is a very special class of light waves – the scattering-invariant light modes, which produce exactly the same wave pattern at the detector, regardless of whether the light wave was only sent through air or whether it had to penetrate the complicated zinc oxide layer,” says Stefan Rotter. “In the experiment, we see that the zinc oxide actually does not change the shape of these light waves at all – they just get a little weaker overall,” explains Allard Mosk.

As special and rare as these scattering-invariant light modes may be, with the theoretically unlimited number of possible light waves, one can still find many of them. And if you combine several of these scattering-invariant light modes in the right way, you get a scattering-invariant waveform again. “In this way, at least within certain limits, you are quite free to choose which image you want to send through the object without interference,” says Jeroen Bosch, who worked on the experiment as a Ph.D. student. “For the experiment we chose a constellation as an example: The Big Dipper. And indeed, it was possible to determine a scattering-invariant wave that sends an image of the Big Dipper to the detector, regardless of whether the light wave is scattered by the zinc oxide layer or not. To the detector, the light beam looks almost the same in both cases.”

This method of finding light patterns that penetrate an object largely undisturbed could also be used for imaging procedures. “In hospitals, X-rays are used to look inside the body – they have a shorter wavelength and can therefore penetrate our skin. But the way a light wave penetrates an object depends not only on the wavelength, but also on the waveform,” says Matthias Kühmayer, who works as a Ph.D. student on computer simulations of wave propagation. “If you want to focus light inside an object at certain points, then our method opens up completely new possibilities. We were able to show that using our approach the light distribution inside the zinc oxide layer can also be specifically controlled.” This could be interesting for biological experiments, for example, where you want to introduce light at very specific points in order to look deep inside cells. (Source: TU Vienna)

Link: Debye Institute for Nanomaterials Science, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands • Non-Hermitian Physics & Complex Scattering, Institute of Theoretical Physics, TU Wien, Vienna, Austria