Horwitz Prize for foundational work on optogenetics

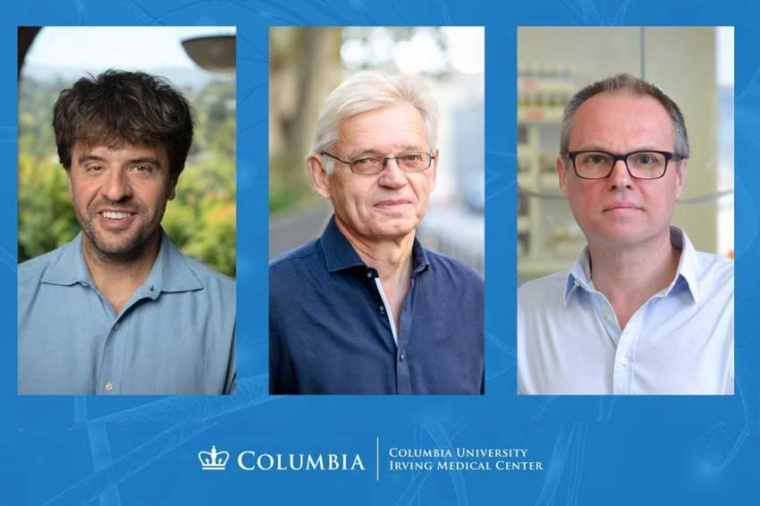

Columbia University will award the 2022 Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize to Karl Deisseroth, Stanford University, USA, Peter Hegemann, Humboldt University, Germany, and Gero Miesenböck, University of Oxford, UK, “for foundational work on optogenetics”. The prize will be presented at a ceremony held in New York City on February 16, 2023.

Optogenetics has revolutionized the study of the nervous system, helped scientists understand how brain circuitry controls behaviors such as learning, sleep, vision, addiction, and movement, and increased the potential for treating diseases like epilepsy, spinal injury, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease.

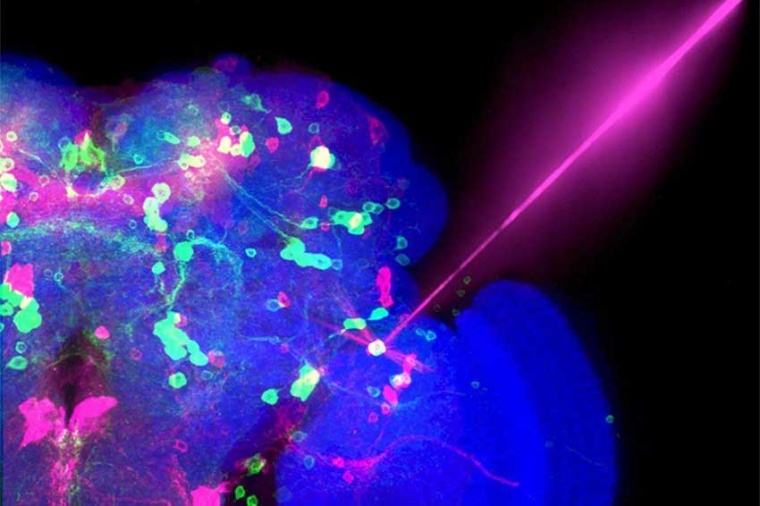

Before optogenetics, the tools scientists had at their disposal to probe the brain were more limited. Using electrical stimulation to excite neurons proved too imprecise, as it also triggered neighboring brain cells. Drugs that targeted neurons acted too slowly and indiscriminately. Optogenetics changed everything because the technique finally let scientists target a set of neurons and control their activity, quickly and accurately.

The name of the technique comes from a combination of the words “opto-”, as the method involves using proteins that are responsive to light, and “-genetics,” because getting the proteins into neurons requires genetic engineering. The proteins used in optogenetics are called opsins, which are found in cells that sense light, like eye cells. Scientists first discovered opsins in the 1800s, but it was not until the 2000s that they were first used as tools in neuroscience experiments.

Optogenetics has continued to evolve after the initial pioneering work of Miesenböck, Hegemann, and Deisseroth. For instance, Deisseroth and Hegemann then together led discovery of the key principles of light-sensitive channel structure and function; they showed it was possible to produce “designer” opsins that respond to different speeds or colors of light, that move different kinds of ions, expanding the range of brain functions that can be studied. Researchers have since implemented optogenetics to study behavior in a wide range of organisms including fruit flies, worms, fish, mice, and even monkeys. Starting out as something that only specialists could use, the method is now so accessible that it has swept through hundreds of labs around the world and transformed the field of neuroscience.

Beyond basic research, optogenetics is also starting to aid the discovery of new treatments. In mouse models, scientists have used optogenetics to activate brain cells to restore memories that appeared to be lost, and relieve signs of depression. Researchers are developing biological pacemakers made from stem cells that can switch the heartbeat on and off with light, potentially offering a relatively complication-free treatment for patients. And last year, scientists used optogenetics to help a blind patient see again. The versatility of optogenetics suggests that many more exciting advances lie ahead.

Deisseroth, Hegemann, and Miesenböck are the 109th, 110th, and 111th winners of the Horwitz Prize, which is awarded annually by Columbia University for groundbreaking work in medical science. Of the 108 previous Horwitz Prize winners, 51 have gone on to receive Nobel Prizes. (Source: Columbia University Irving Medical Center)

most read

Machine Safety 2026: The Five Most Important Trends for Eutomation Engineers

Digitalization and automation continue to drive mechanical engineering forward - and with them, the requirements for functional safety and cyber security are increasing. For automation engineers, this means that machine safety is becoming a holistic concept.

Lapp founds its own company in Taiwan

The Lapp Group has assumed operational responsibility for the cable business in Taiwan, which was previously managed by DKSH Business Unit Technology.

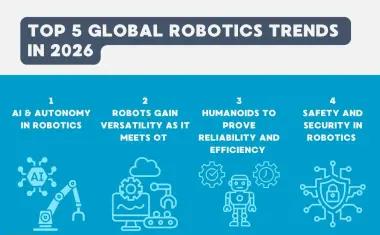

5 robotics trends for 2026

The International Federation of Robotics reports on the five most important trends for the robotics industry in 2026.

Basler AG: Change in the Management Board and new CTO position

Long-time CEO Dr. Dietmar Ley will leave the Executive Board at the end of 2025